Jasmine Adams reflects on the heart of every home

Did Peranakan families have “clean functional kitchens” which were championed by Helen Campbell, social reformer and home economics lecturer in the late 19th century?

This is what Ronald Knapp in his book, The Peranakan Chinese Home, claims: the Anglophile behaviour of the Peranakans who built their own homes included adopting the concept of bright and airy rooms in lieu of the “cluttered, dark and smoky” kitchens which still exist in ancestral homes in Southern China today.

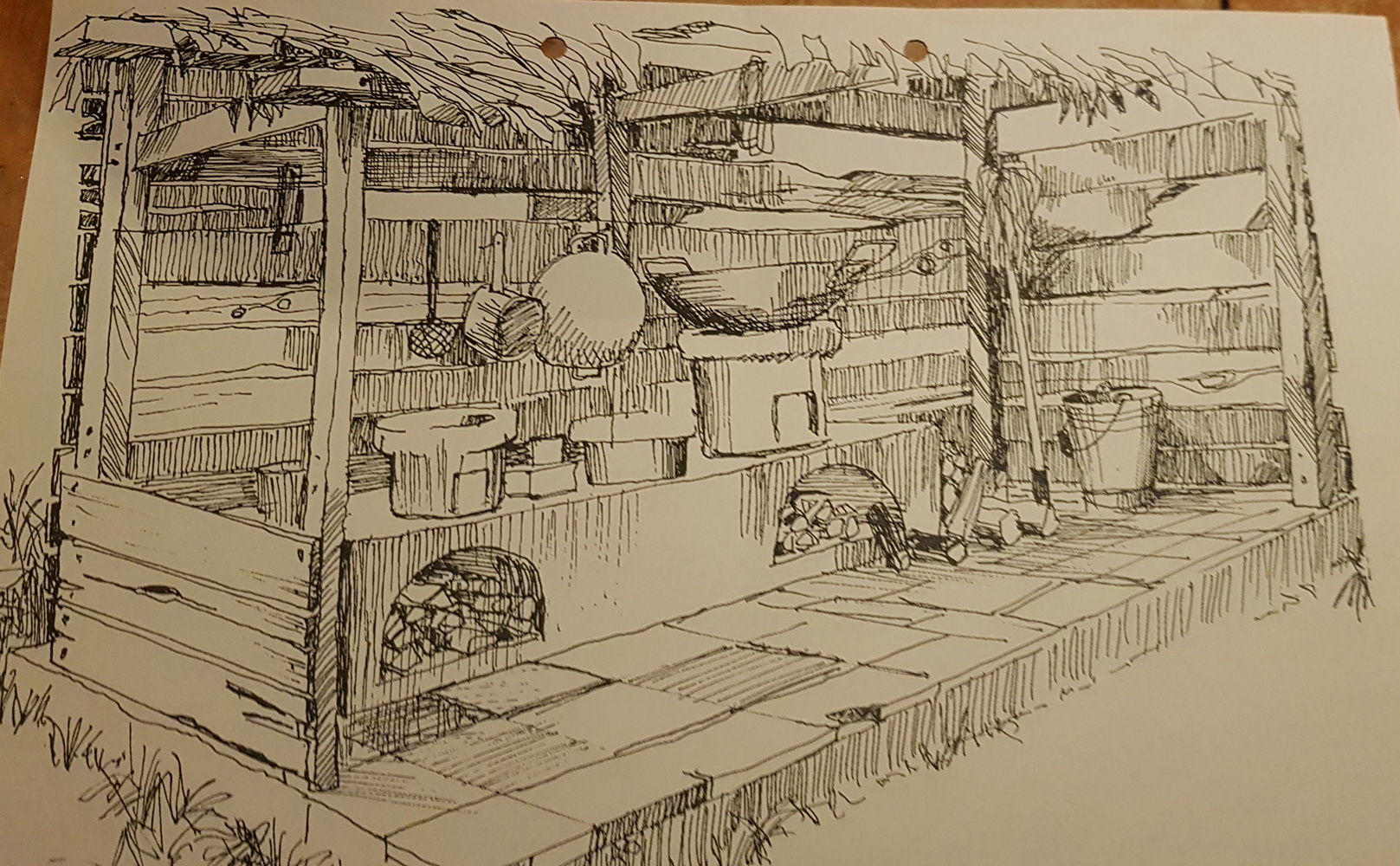

My memory of our kitchen in the shophouse at Marshall Road where I grew up was that it was as bright and airy as any kitchen could be. In fact, it was literally open air, with only part of the kitchen area sheltered. More than half of the kitchen was open to the sky, and it was only the outhouse, bathroom and area over the dapor which was sheltered.

Knapp, being Western, could only conceive of the kitchen as a room, but dapor – the Indonesian / Malay word – is an all-encompassing term that includes the plinth on which the charcoal or gas stoves stood or were built upon. It can even refer to standalone stoves or a range of them. Dapor further extends to mean the area in which the it is located, which in Western terms would refer to the kitchen.

Today, the light touch of a finger ignites invisible flames, but the dapor of yesteryear was treated like a living thing, as it had to be fed and attended to constantly.

Yet Peranakan women could manage a magnificent assembly of elaborate dishes on the humblest of stoves. On occasion, some were arranged in the area next to the air well, and when there was the need to cook many large pots of food, more charcoal stoves borrowed from cooperative neighbors were tended to in the back lane just outside our back door.

While my grandmother was alive, all soups had to be brewed on the charcoal stove. It was no higher than two feet, red and cylindrical, and had a pair of tiny sliding doors in the front, no bigger than the size of two cigarette packets, to accommodate a pair of tongs for arranging the charcoal within and pushing out the excess ash.

The thick-lipped circular top of the stove was rudely ridged, with three rounded protrusions on which a well-seasoned wok or dented enamel pot would nestle, and, in the case of the wok, with enough of a gap to have traction and swirl when the occasion demanded.

A frequent visitor to our kitchen was a lean, yet muscular charcoal delivery man, burdened with a 20-pound sack of charcoal, his shoulders covered with soot like a sprinkling of black dandruff, and his singlet no longer retaining any trace of its cottony white origins. My grandmother would direct her anger at whoever forgot to order the charcoal, but once he arrived, all was forgotten in the mad rush to re- ignite the stove with the stumps of fire-starter and charcoal logs.

Should any of us children happen to be within shouting distance and be compliant enough to respond, a fan made with palm fronds would be thrust in our hand, with a no-nonsense instruction to swing it back and forth with all our might until flames shot high from the opening!

Fanning was not the only issue, but as the charcoal stove stood on the ground, we had to do this sitting on our haunches and squat, precariously balancing on our clogs.

It is with nostalgic regret that I never imposed these tasks on my children, nor will I venture to try this on my granddaughter. Not only would they quash any suggestion that soups boiled lovingly on a slow burning charcoal flame would have any enhanced taste or nutritional value, but I would be bombarded with Google search results on how orh kim – the Hokkien name for charcoal – cannot possibly affect the contents behind the thick stainless steel walls of cooking pots.

I think that my generation had the best of both worlds, being able to savour the best flavours and only involved in a fraction of the labor, and yet now, just having our dapor lit with the mere touch of a finger.