Meet Mek and Awang of Terengganu and Kelantan

Nyonya Cynthia Wee-Hoefer makes a week-long trip to Terengganu and

Kelantan to meet a unique divergent offshoot of Peranakan Chinese, unveiling

an intriguing history of migration, integration, and a waning hybrid culture.

This is part one of a three-part story.

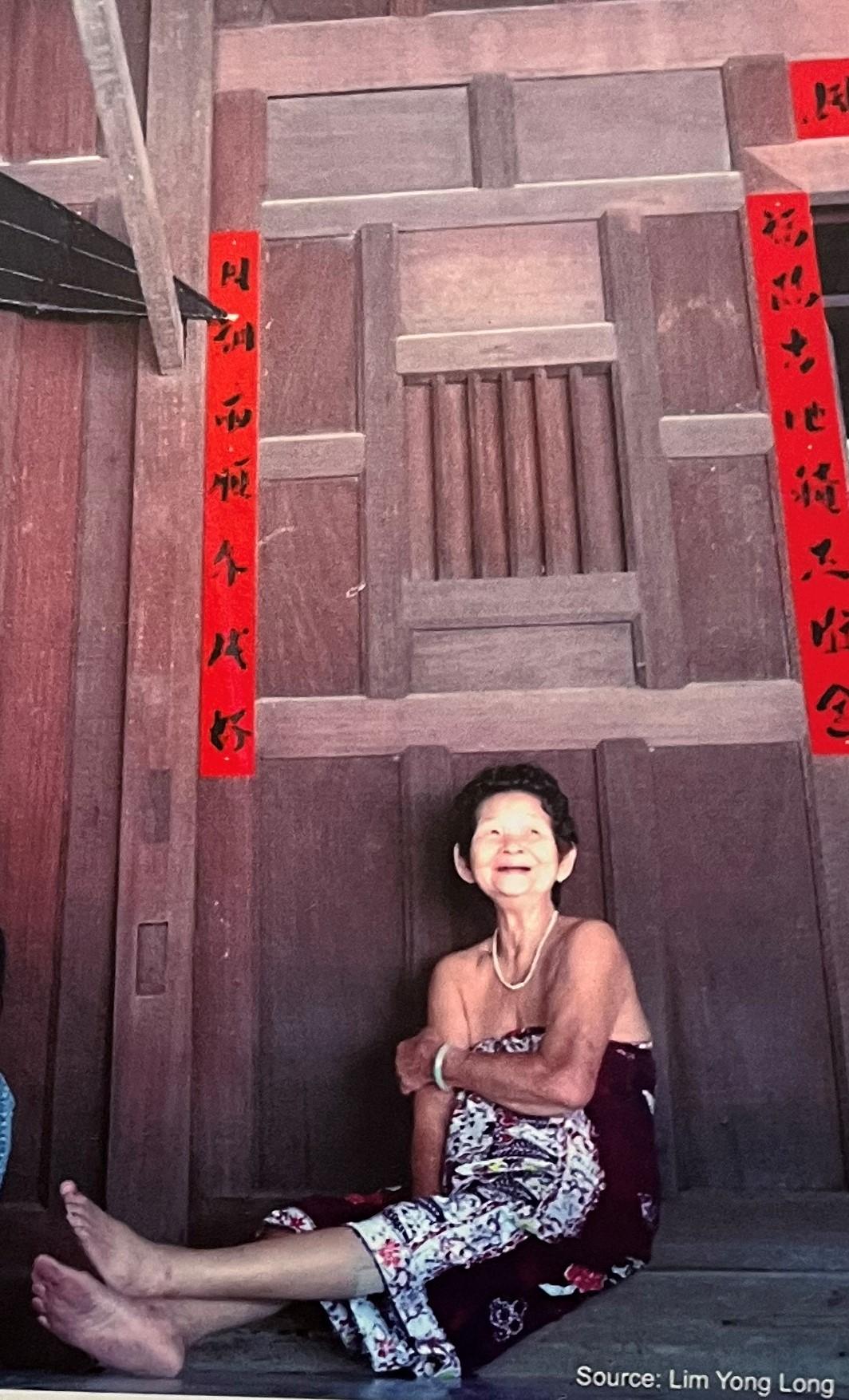

Let me introduce you to Mek and Awang of Kelantan and Terengganu. In the

ordinary Baba Malay patois you would address them as nyonya and baba, or

encik. Not in this north-eastern state of peninsular Malaysia.

Not only are the women referred to as Mek, and the men as Awang, some of

the Kelantan Chinese have taken up Malay names unabashedly. Awang Hasan lives happily with the title, with family members and neighbours referring to him as such.

On my recent trip to Terengganu and Kelantan, I met up with the leaders of the Peranakan Cina associations to forge a better understanding of this distant community.

Within the Peranakan Chinese, there are distinct features that separate them

from the rest of the former Straits Settlement Baba strongholds in Penang,

Melaka and Singapore. My first encounter with the locals was in Kota Terengganu at gallery Terradela, run by the owner Alex Lee, himself a Peranakan Chinese. My travel companion and I put up at the beautiful Terrapuri Heritage Resort of wooden royal houses refurbished by Alex.

Among other displays in Alex’s gallery was a tall floral arrangement of stacked and overlapping leaves of the Kadok, or Piper Sarmentosum, on a table. This charming array is presented by a groom to his chosen bride’s family as a symbol of courting (adat meminang).

Alex explained that the higher the arrangement of Kadok leaves, the more

prosperous the match will appear. In other Baba households throughout Southeast Asia, the tapak sirih (betel leaf container) is offered. This is a Malay tradition adopted by the Straits Chinese.

Dr Wee Tiong Wah, president of the Persatuan Peranakan Cina Terengganu,

was quick to point out that he grew up in Singapore studying at Raffles College before returning to Kuala Lumpur to take up a degree in dentistry. Dr Wee’s late wife also hailed from Singapore.

He leads the fledgling seven-year-old association of less than a hundred

members.

After preliminary introductions, we sat down to a lunch of delicious Kelantan

laksa, nasi dagang (curried fish and flavoured rice), several appetisers of young papaya, a jicama (turnips) and bangkwang (yam bean stewed in garlic and fermented soya bean paste) dish, a dish of cucumber and carrot shreds eaten with fried fish keropok (fish crackers) and sauces, served alongside the cigar-shaped fish paste lekor and sambal belacan dip.

A rice wafer toasted over a flame and filled with sweetened grated coconut

was a most interesting dessert.

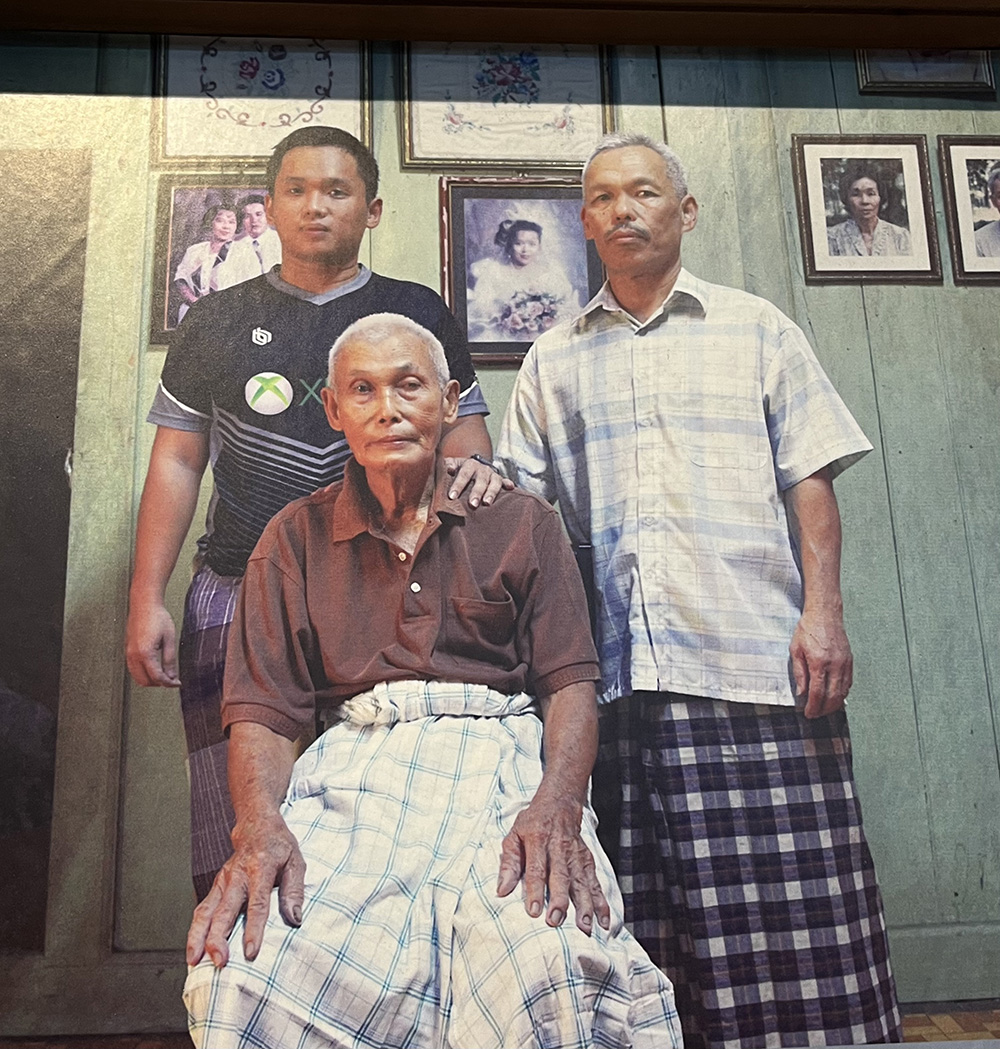

“It was only in about the last 10 years that we dug up the past about ourselves and our history. We never thought of ourselves as Peranakan Chinese,” said Yap Chuan Bin, deputy president of the Association.

Yap places himself as the 11th generation of the Chinese seafarers who landed on the northeast Malayan coast and established settlements more than 250 years ago. Some accounts state their arrival earlier in the sixth century, but this cannot be verified.

Presently, Yap counts about 2,000 Peranakan Chinese still residing in the

Terengganu state.

The diminishing number of the community can be attributed to the exodus of the younger, educated generations to the big cities and abroad setting up their own families away from home.