By William Gwee Thian Hock

Babas and nyonyas were generally perceived as being unable to speak Chinese at all, managing only a smattering of spoken Hokkien or Cantonese dialect. Any Peranakan capable of reading and writing Chinese was rare. However, a change came about in the 1930s when some babas and even nyonyas went to school to study Mandarin in their free time.

It began in my mother’s former childhood home. No 74 Prinsep Street was once owned by my maternal grandfather, Seow Ewe Un. My mother Leong Neo, the youngest of his six children, was seven years old in 1919 when the family moved into this home where she grew up until 1927 when she married and moved to Cuppage Road. Although the Prinsep Street dwelling had a single address, it actually comprised three two-storey terrace houses which only in later years were separately addressed.

This 3-in-1 dwelling conveniently housed grandfather’s family of 10. They comprised maternal great grandmother, grandfather (already widowed), his four sons, two daughters-in-law, his two daughters and a domestic staff of three cooks, two servants,two slaves and a watchman. Maternal grandmother had passed away even before the family moved into PrinsepStreet.

Mother became an orphan when grandfather died of tuberculosis a few years before she married. Great grandmother then took over as matriarch to head the household. After mother married and was the last grandchild to move out, great grandmother found the house too large for herself. She sold the house and moved into a smaller home at Emerald Hill Road, where she spent the rest of her days.

Around this time, a Chinese scholar Huang TseTan, BA, noticed many Singaporean Chinese (then popularly then known as Straits Chinese) were unable to speak, read or write Chinese. Apart from the Babas,other local born Chinese who were educated in English, spoke a Chinese dialect at home but could neither read nor write Chinese. There were also the dialect speaking but non English-educated Chinese who possessed a very low level of Chinese education.

From childhood home to school

Huang decided to Office of the remedy the situation and embarked on a campaign to bring Chinese education to these people. He bought over mother’s childhood home. Huang found it just right for a school to cater to working adults. He founded and became the first principal of The Singapore Chinese Mandarin School, which opened its doors to students in 1931.

Huang listed a dozen objectives, the main of which was to impart written and spoken Chinese to local Chinese as well as foreigners who might be interested to study Chinese. Students of any nationality above 15 years of age were welcome to enrol for courses at Beginners, Intermediate and Advanced levels. Each course would last about a year, taught in Mandarin and explained in English.

The curriculum included subjects such as Chinese reading, Mandarin conversation, phonetics, formation of sentences, letter writing, essay writing, Chinese history and geography. Students were required to attend two lessons each week, each session lasting about two hours (5.15pm to 7.00pm or 7.15pm to 9.00pm). They had a choice of three classes: Class A on Mondays and Thursdays, Class B on Tuesdays and Fridays, and Class C on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The fee was $2 a month.

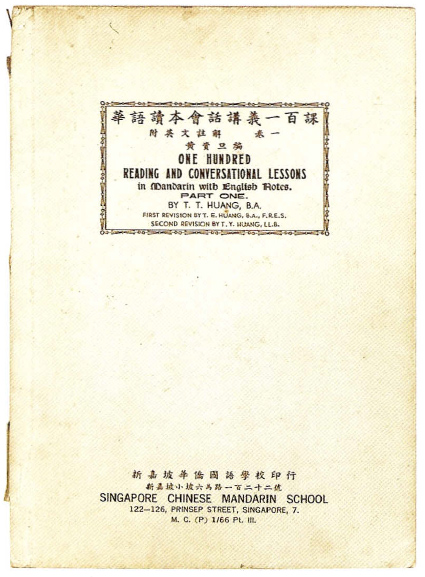

A year before the school commenced, Huang authored and published a bilingual textbook specially for the school, titled “One Hundred Reading and Conversational Lessons” in Mandarin with English notes. A second textbook was published between 1931 and 1932. However, the third and fourth textbooks that appeared in 1933 and 1934 respectively, bore the name of Huang Tse Yen, LLB as author. This may have been due to health reasons which had prevented Huang Tse Tan from authoring them.

A 1938 souvenir maga zine of the school con tained a photograph of him with the caption: “The Late Mr Huang Tse Tan, BA, (Former Principal and Founder)”. The four different textbooks written in the same format were used by the school’s students at different levels of their study. Book 1 (Part 1) was for Beginners, Book 2 (Part 2) was for Intermediate and Books 3 and 4 (Parts 3 and 4) were for those in the Advanced classes. All these books went into several reprints, for instance Book 1 had its 18th edition in 1970. Huang Tse Tan’s successor, Huang Tse Yen, published the school’s textbooks Parts 3 and 4, and became the school’s next principal. He kept alive his predecessor’s dream of promoting the study of Mandarin and tirelessly steered the school from strength to strength until it finally closed doors 40 years later.

Prominent Baba students

Despite running only evening classes, the school attracted an endless stream of students and was obviously a prestigious institution. By its seventh year, it counted among its many patrons some of the most prominent Singapore Chinese personalities of the day, including Dr Lim Boon Keng, Seow Poh Leng, Aw Boon Haw, Lee Kong Chian and Dr Chen Su Lan.

Apart from Mr and Mrs Huang Tse Yen themselves, the school’s teaching staff were of high calibre. They included Huang Tse En, BA, F.R.E.S., and Tsiang Ke Tsiu (Chiang Ker Chiu) a prolific author of teaching textbooks such as “Mandarin Made Easy” and “Progressive Mandarin Reader” and books on different Chinese dialects. Tsiang was actively involved with another teaching institution at 56 Short Street called the Chung Hwa Mandarin Institution which was founded in 1939. This institution offered Mandarin for the Cambridge Examination and also Hokkien and Cantonese language lessons.

The highlight of the School’s success story was its steady stream of students and especially its ability to attract Babas and non-Chinese students to sacrifice after-office hours twice a week to go to class. Some students gave up after two to three months while others persisted for three to four years or even longer. Those who gave up early were probably Babas and English-educated Chinese who might have found Mandarin beyond their ability to cope with. The non-English-educated locals who prematurely abandoned their Mandarin study might have found the English medium of instruction a disappointing stumbling block.

Close to 1,400 students of both sexes crossed the school’s threshold within the first seven years. Their ages ranged from 15 to 65, with 19 years old being the majority. They came from diverse walks of life, ranging from clerks, to doctors, lawyers, detectives, magicians, police inspectors and even a professor from Raffles College (Prof Alexander Oppenheim). Their nationalities were as varied; almost akin to that of a mini-League of Nations! There were Chinese (1372), British (21), Indians (12), Eurasians (9), Ceylonese (9), Dutch (9), Siamese (4), Swiss (4), Germans (3), Malays (3), Javanese (2), Australians (2), Czechoslovakians (2), a Korean (1) and a Jew (1).

The school seemed to have had a special appeal to the Baba community. Babas and nyonyas responded to the call to study Mandarin although there was, frankly, little reason for them to do so because, at the time, it was English and not Mandarin that would open every door in colonial-ruled Singapore. Undoubtedly, deep inside, the Babas were and are still Chinese.

My father, Gwee Peng Kwee, his peers and relatives were among those who had spent some time in the school. Although father did not complete the course, he managed a little spoken Mandarin. This was rather surprising because later on he became fluent in the Hokkien and Teochew dialects, both of which he had picked up after his struggle with Mandarin.

Other Baba contemporaries who also studied at the school were practically the who’s who of the Baba community of the 1930s, such as Khoo Teng Eng, Tan Soo Wan, Chia How Ghee, Khoo Eng Teck, Chan Wah Keng and many more. (It is said that former President, the late Dr Wee Kim Wee, had also once been a student at the school.)

A nyonya mosaic

In later years, when I had the privilege to meet the school’s retired long-serving principal Huang Tse Yen, he mentioned with well-deserved pride that his former pupil, Chan Wah Keng, stopped reading English newspapers after coming under his tutelage and only read Chinese newspapers thereafter. Wah Keng’s son, my former childhood schoolmate Thai Ho, revealed to me that his father had persisted with his Mandarin study in the school long after he was well past the prescribed courses and was the sole student in the class right up to the eve of the school’s final closure in the 1970s. Huang Tse Yen, the educationist, must have indeed been a very powerful source of inspiration! Nyonyas also gave their support and in the school’s early register there were already three obvious nyonya names on record: Lim Chee Neo, Lim Chye Neo and Wee Hock Neo.

In the early 1980s when I embarked on my project to write a book about mymother’s childhood in her Prinsep Street home, and needed photographs of the premises to serve as illustrations, I was shocked and disappointed to discover that the building had been demolished a couple of months earlier. After a difficult search, I managed to establish contact with Mr Huang Tse Yen. He had already retired by then.

On my first visit to his home, I brought my mother along. We were very warmly welcomed by Mr Huang and charming and gracious Mrs Huang. After learning of my reasons to have photographs of the school building and the fact that my mother had grown up in that same building, Mr and Mrs Huang responded instantly and generously. They gave me all the photographs still in their possession.

Without this gift, my book “A Nonya Mosaic”, published in 1985, would certainly have been much poorer in quality. Not many months after my mother passed away in 1995, this scholarly gentleman, who had so diligently pioneered the study of Mandarin particularly among the Babas for the best part of his life, also departed from this world. In a way, this brief article is my humble and belated tribute to him